The pandemic threw many established healthcare norms into stark relief, accelerating changes that once seemed distant possibilities. My own experience-being informed I would be ‘nursed on a virtual ward’ during COVID-19s frightening and uncertain first wave-transformed the abstract concept of decentralised care into a deeply personal reality. While familiar with hospital processes as a nurse, navigating this new model as a patient was disorienting, blending the undeniable comfort of my own home with a profound sense of isolation and a unique reliance of the then-nascent technology. It was a stark illustration of a healthcare system under duress, innovating at speed.

This episode of The Educated Guess will explore this significant systemic movement towards ‘hospital at home’ and other decentralised care models, a shift driven by urgent hospital pressures and catalysed by rapid technological advancement. Drawing upon my dual perspective – the insights gained from the frontlines of nursing, alongside the lived experience of receiving care within such an evolving system – we will dissect the drivers behind this transformation, the technologies that underpin it, and critically examine both the compelling potential and the inherent pitfalls. The aim is to foster a deeper understanding of how these models are reshaping healthcare delivery and what is required to ensure they are safe, effective and truly – patient-centred.

My Virtual Ward Journey – A Personal Case Study

Less than two weeks into the UK’s first national lockdown in March 2020, the then-unfamiliar symptoms of COVID-19 took hold and rapidly worsened. Following a discussion with my GP, I found myself “admitted” to what was, in essence, an early form of a virtual ward, though it wasn’t explicitly named as such back then. The initial process felt surprisingly straightforward: a pulse oximeter and symptom tracking sheets were delivered to my home, my contact details were taken, and the remote monitoring protocol was explained. My nursing background meant using the oximeter and understanding the readings was second nature. Yet, I was acutely aware that for many, this small piece of technology, especially without in-person guidance, could be a source of anxiety – a stark reminder of the digital literacy challenges that remain a known barrier to the effective implementation of virtual wards today. Beyond this, the technology was minimal; with no continuous telemetry, care relied entirely on my ability to report symptoms over the phone. It also struck me then, as it does now, how difficult it would be to absorb instructions for new technology when one is acutely unwell and struggling with symptoms. In such moments, the ability to effectively learn is compromised, underscoring the critical need for family or carer involvement in any technology training.

Communication with the healthcare team was entirely by telephone, with a daily call that, for the initial period, felt sufficient. However, when my condition deteriorated sharply three days later, a critical flaw in this early model became terrifyingly apparent: there was no clear escalation plan. It was only through discussing my worsening symptoms with my own nursing colleagues – a recourse not available to everyone – that the severity of my situation hit home, prompting me to call an ambulance myself. While the daily calls had offered a degree of reassurance, their limitations became starkly clear in a crisis. My previous experiences as an inpatient had always involved clear pathways for escalating concerns, a safety net of professionals immediately accessible. In this virtual setting, that net felt absent, with the ambulance service seeming like my sole point of recourse. The interactions, though well-intentioned, often felt impersonal, lacking the tangible human connection that physical presence provides and that compassionate care seemingly relies upon.

While the monitoring didn’t feel intrusive and offered some baseline reassurance, the isolation was overwhelming. With significant breathing difficulties, even speaking on the phone became an exhausting ordeal, preventing any truly meaningful exchange about my condition. The comfort of my own home, initially a solace, began to feel like a prison. Food was left at my door, human contact was non-existent, and even simple tasks like walking to the toilet felt fraught with the risk of collapse, unsupported. Crucially, the COVID restrictions at the time meant no opportunity for my family to be involved in my care, a support system that, in non-pandemic circumstances, would have been vital. I felt a degree of empowerment from diligently tracking my symptoms, yet when faced with deterioration, this quickly morphed into a heavy burden of responsibility – one I’m not sure I was equipped to handle. I vividly recall my fear of hospitalisation leading me to downplay the seriousness of my symptoms, allowing them to worsen. My nursing experience tells me this is a common patient behaviour, born out of fear. Had I been in a traditional hospital setting, the subtle but critical signs of my decline would likely have been observed and acted upon far sooner. Ultimately, being left to essentially coordinate my own emergency admission made me question the very purpose of the virtual ward in that critical moment: if the onus of escalation fell entirely on me, what safety net was truly in place?

The Promise and Potential: Envisioning a Matured “Virtual Ward”

While the COVID-19 pandemic certainly accelerated their adoption, the primary drive behind virtual wards, (also known as ‘hospital at home’ services), originated well before the crisis, stemming from the persistent and intensifying strains on traditional hospital systems (Hakim, 2023, Nuffield Trust, 2020). For years, Accident & Emergency (A&E) departments across the UK have faced immense strain, with waiting times frequently exceeding targets and reports of “corridor care” becoming distressingly common. A&E becomes the point of access for acute care, where people are assessed and admitted to services, including those who cannot gain access to care in the community, often as a place of safety or for social support. With 41% of all A&E admissions for conditions that could be managed elsewhere, the need to free up resources is greater than ever (RCEM, 2022). Patient demographics are also evolving; with higher numbers living to their late 80s and beyond, often developing multiple complex chronic diseases, which provides clinical complexity in times of acute illness (ONS, 2023, NHS Digital, 2024). Data suggests that 26 million people currently live in the UK with at least one long term condition, which highlights the need for sustainable, suitable options for acute and acute-on-chronic conditions (NHS Digital, 2024). With elective care waiting lists and patient flow issues around hospitals nationwide, the need for innovative models to manage hospital capacity, improve patient flow and deliver care more efficiently has become undeniable (NHSE, 2016).

COVID-19 acted as a powerful catalyst, forcing the rapid adoption and scale-up of remote care models out of sheer necessity. However, their continued expansion post-pandemic, underscored by NHS strategies aiming to establish significant virtual ward capacity – for instance, with earlier ambitions for around 40-50 beds per 100,000 people and current capacity of virtual wards reaching 12,724 patients – demonstrates a clear recognition of their enduring value (NHSE, 2023, NHSE, 2025a). Virtual wards are now increasingly seen as a vital component in the strategy to alleviate hospital pressures, offer more personalised care, and create a more resilient healthcare system (NHSE, 2025b). It is against this backdrop of urgent need and strategic commitment that we can, and must, envision what a truly matured and optimised virtual ward service should look like.

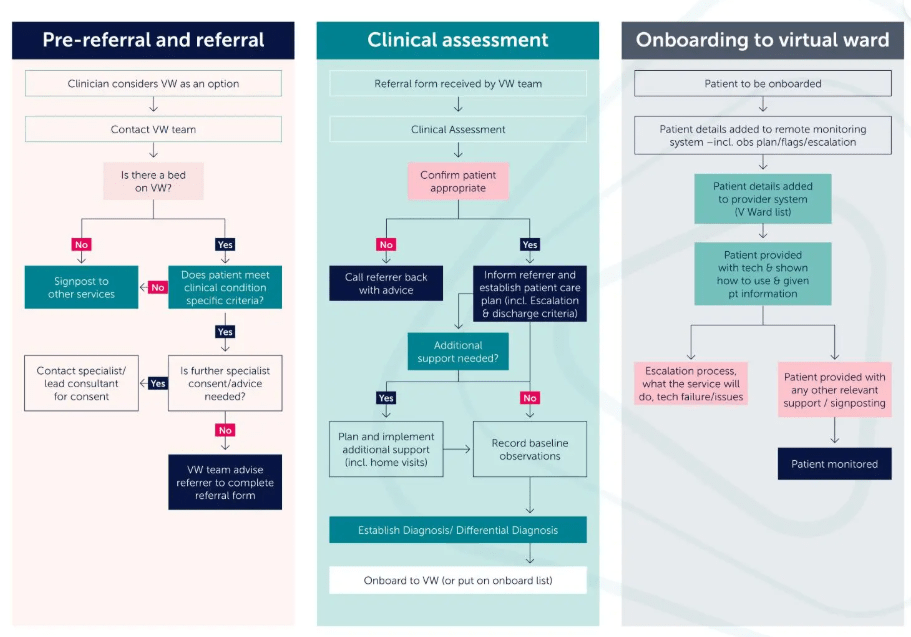

Source: Hakim 2023

Reflecting on the challenges encountered in those early pandemic days, the vision of a truly matured “virtual ward” or “hospital at home” service offers a stark, hopeful contrast. Such a service, thoughtfully designed and robustly implemented, wouldn’t just be about remote monitoring; it would represent a holistic evolution in how we deliver and experience acute care. For the patient, the benefits could be profound, directly addressing many of the anxieties and shortcomings I, and undoubtedly others, have faced.

Imagine a care experience where the comfort of one’s own home genuinely supports healing. This means undisturbed rest, free from the relentless noise and interruptions of a busy hospital ward, facilitated by wearable sensors that transmit vital telemetry seamlessly, often without conscious patient input. For older patients or those with dementia, remaining in familiar surroundings can significantly reduce the risk of delirium, a common and distressing condition often experienced with acute illness or hospital admission (NHS Inform, 2024). The significantly lower risk of contracting hospital-acquired infections and the dignity of not being cared for in a corridor or overcrowded wards are also powerful advantages. Beyond physical well-being, such a model promises greater patient autonomy and deeper involvement in their own care. Treatment becomes truly personalised, delivered within a comforting, known environment. The potential for swift multidisciplinary team input, without the delays of transfers or outpatient queues, could revolutionise how quickly specialist advice is integrated.

Communication, too, would be transformed: envision readily accessible text-based chat systems for day-to-day concerns, alongside scheduled virtual consultations. Crucially, these would be enhanced by high-quality video conferencing, offering clinicians the ability to conduct essential visual assessments – a world away from the limitations of a simple phone call – and equally importantly, fostering a more personal connection, the value of which cannot be understated in providing compassionate care. This visual link helps to restore some of the vital human touch that can be lost in purely remote interactions. Furthermore, a sophisticated, adjustable alert system would empower clinical staff to proactively escalate care the moment a patient’s condition deteriorates, providing the safety net that felt absent in my earlier experience. And, so importantly, these matured models would actively integrate family members and caregivers, recognising them as vital partners in the care journey, alleviating the profound isolation I felt.

The benefits extend beyond the individual patient, offering systemic advantages for the NHS. Increased hospital capacity and reduced lengths of stay become achievable, freeing up acute beds for those who most critically need them. This, in turn, can lead to significant cost efficiencies and a more effective deployment of precious healthcare resources. Furthermore, well-designed virtual wards can foster improved staff satisfaction, offering new, flexible, and technology-enabled ways of working that can be both efficient and rewarding. The wealth of data generated also opens doors for groundbreaking research and data-driven insights, paving the way for more proactive and predictive care models in the future. If all these elements – patient-centred technology that includes robust visual communication, seamless information flow, robust safety protocols, and integrated multidisciplinary support – were thoughtfully implemented, the experience of being cared for outside traditional hospital walls would indeed be significantly, and positively, transformed.

This inherent adaptability, allowing virtual wards to be tailored for diverse groups of any age with the right clinical support and careful implementation, truly underscores their far-reaching value and transformative potential as a core component of future healthcare.

Hurdles and Headwinds – Challenges to Widespread Adoption

While the vision of a matured virtual ward is compelling, achieving it requires us to navigate significant hurdles. My own experience, even in its nascent form during the pandemic, threw several of these challenges into sharp relief, highlighting areas that demand careful and considered solutions if these models are to truly flourish.

A primary concern in the rollout of virtual wards is ensuring digital equity. The promise of technology-enabled care means little if access to the necessary tools and reliable connectivity remains unevenly distributed, an issue UK reports consistently flag. While some NHS Trusts commendably pilot virtual wards by providing patients with the required technology- from pulse oximeters and blood pressure monitors to scales for heart failure patients – this vital step itself introduces further considerations (HINSL, 2021, BTH, 2024). Firstly, requiring Trusts to fund these numerous devices provided adds a significant cost burden to their implementation efforts. Secondly, even with devices provided, this doesn’t fully bridge the broader digital divide. A crucial aspect of this divide is universal, reliable internet access. While an impressive 99.8% of UK homes have decent internet, an estimated 0.2%, roughly 136,700 people, remain disconnected (Ofcom, 2024). This disparity particularly impacts those in geographically remote locations or those who cannot afford connectivity costs, creating a significant ethical issue. Ultimately, these gaps risk excluding precisely the demographic – often older, with multiple chronic diseases, or living alone – who could greatly benefit from home-based care yet concurrently face the highest risk of digital exclusion.

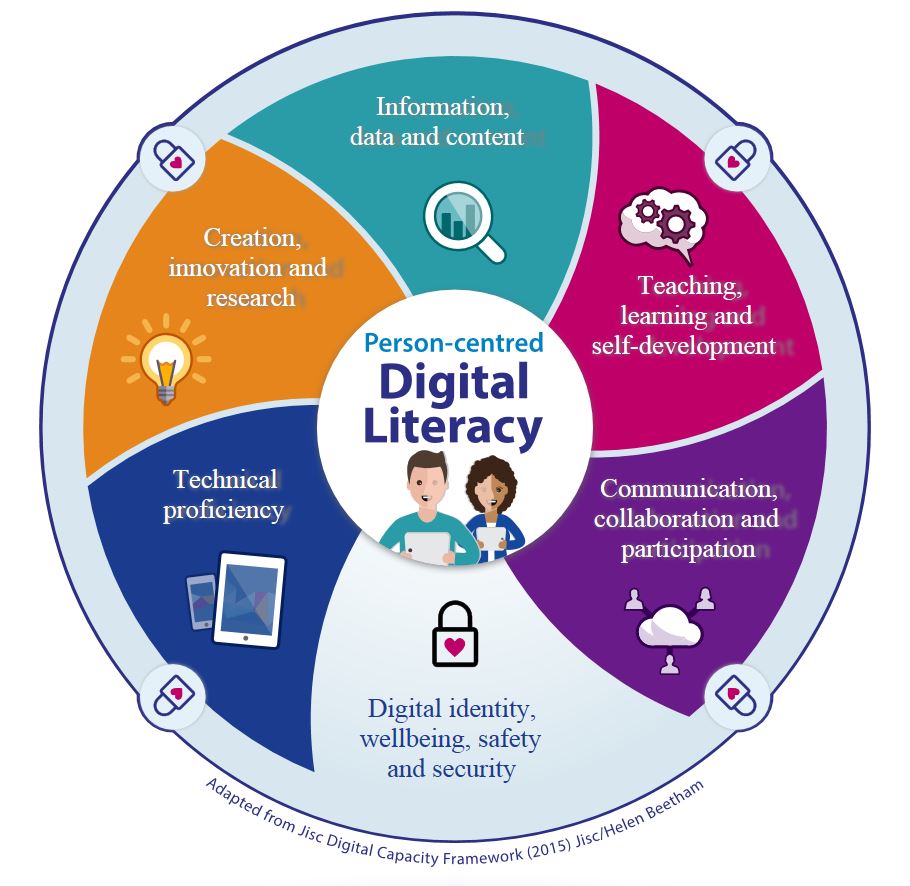

Beyond the issue of access lies the equally significant hurdle of digital literacy – the actual skills and confidence to use technology, even when provided. The scale of this challenge is stark: an estimated 16.8 million adults (around 20%) in the UK lack foundational digital skills, with 4% unable to perform any basic digital tasks, a deficit most common among those over 75, the retired, or those living alone, who may be prime targets for virtual ward patients (LBUKCDI, 2024). This widespread skills gap means that the educational undertaking for NHS Trusts, as they implement virtual wards, is likely far more substantial and resource-intensive than often anticipated, especially when patients are grappling with acute illness and their capacity to absorb new information is diminished. My own relative ease with a simple oxygen saturation probe, thanks to my nursing background, is not a universal experience; for many, new technology can be a source of anxiety. Complex or new technology, introduced during illness can be a source of profound anxiety. This highlights a critical necessity: education and support must extend beyond the patient to encompass their family members or carers, who are often vital in assisting with technology and supporting engagement with remote care. Furthermore, the digital proficiency of NHS staff themselves is a cornerstone of safe and effective implementation, demanding ongoing attention to ensure they are confident and competent users of these evolving systems. Addressing these multifaceted literacy needs across patients, their support networks, and healthcare professionals is therefore essential for virtual wards to achieve their full potential (HEE, 2017).

Source: RCN Every Nurse an E Nurse.

Beyond patient access, equipping our healthcare professionals for this new frontier is paramount. Remote assessment, nuanced virtual communication, and adept technology management are skills not yet routinely embedded in undergraduate or postgraduate training across healthcare professions. This necessitates a significant focus on developing not just technical proficiency, but also critical assessment and decision-making skills tailored to remote settings. Existing roles and workflows will need rethinking to ensure patient safety and avoid duplicating effort, acknowledging that even the most intuitive user interface involves a learning curve. As an educator, this strikes me as a powerful opportunity: the very technology enabling remote patient care could simultaneously be leveraged to offer remote clinical-decision making support to more junior colleagues, whether they are face-to face with the patient or new to remote practice themselves. This approach could foster invaluable professional development whilst upholding patient safety, particularly when managing complex cases.

Then there’s the bedrock of reliable infrastructure. Anyone who has worked with internet or digital tools knows that power and Wi-Fi can be intermittent, particularly during bad weather. Mobile signal needed for remote uploads can also vary, with 4G/5G blackspots persisting in community settings. Despite ‘paperless’ targets not being met, the NHSE&I now expects the NHS to reach a ‘core level of digitisation by 2024’ with important information routinely available to clinicians when and where they need it (NAO, 2020). This is a significant challenge when IT infrastructures vary across Trusts within the same geographical regions, let alone nationwide. Developing secure, interoperable systems that can safely incorporate innovations like AI and machine learning – for trend analysis- is essential for patient safety and for seamless integration of remote monitoring data. This is a daunting task, but one that requires careful consideration, incorporating the needs of the staff using them to be effective and support significant and sustainable digital transformation nationwide.

Above all, patient safety and robust governance are non-negotiable. Although my own experience with a new and unknown disease is far from the norm, it does highlight the need to meticulously select suitable patients for virtual wards, and clearly defined, readily actionable emergency response pathways. Whilst virtual wards are an essential component of NHS strategy, we must recognise that hospital care will still be required. Perhaps not by every patient, but occasionally, there will be limits to the care a virtual ward can provide. Selecting the appropriate patients for hospital and virtual wards will be essential to maximise patient safety and reduce hospital burden. Ensuring appropriate clinical support and skill mix to ensure safety as with traditional wards, is essential and the approach to skill mix can vary depending on patient need, particularly as virtual wards can include patients of any age or medical specialism. Ensuring unwavering clinical accountability and data security, including end-to-end encryption to meet GDPR guidelines and protect against cybersecurity threats, is fundamental to meeting both legal and professional requirements.

Sustainable models of funding and commissioning are needed to fund these new pathways. Although NHSE request new virtual ward beds, it remains down to the individual trusts to develop these strategies, and the funding required for them. There will need to be funding made available to fund the technology and education needed to start these functions.

Building trust in remote care models among both patients and staff. Overcoming the perception that in person care is always superior. I witnessed some of these issues as a patient, but the IT technology and patient safety remains the key factors from my personal experience. I think all of these issues would have made me feel more secure.

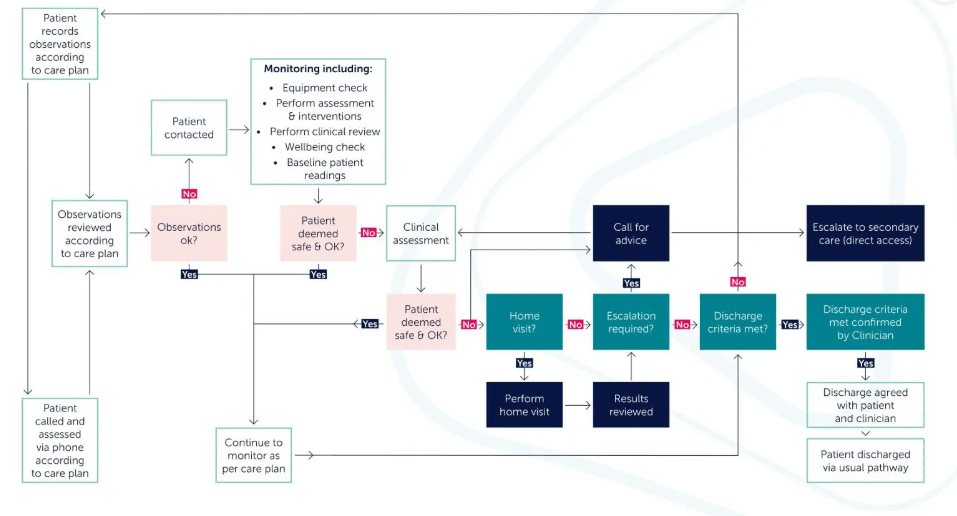

Source: Hakim, 2023. Suggestion of how Virtual Wards Monitor Patients.

The Path Forward – Realising the Vision Responsibly

As I’ve mentioned earlier, thoughtful implementation is key. We must resist the urge to rush out a system in the effort to meet targets. Co-design with patients and clinicians is ultimately key to making it easy and valuable to use. This also helps target some issues in user interface as well as data analysis and note taking and ensures that it is accessible to everyone.

We must learn from pilot studies, iterating designs and developing a continuously improving approach as technology improves, it facilitates use for the future. Robustly evaluating outcomes ensures it is fit for the population it is targeting and the unique geographical needs of the individual trust. Phased and evaluated rollout represents a scientific and cost-effective approach to implementation.

Ensure that technology augments rather than replaces compassionate, person-centred care. Not everyone will be able to cope or do well with this type of treatment/monitoring. When a face-to-face visit is required, a team of suitably qualified professionals will be needed to visit patients. We also need to be mindful that with all this data, we still need to treat the patient and not the numbers.

Funding is essential. Government and NHS funding needs commitment, infrastructure and clear policy frameworks. We also need to consider social care – as this can often be a significant contributor to unnecessary hospital admissions. We also need NHS oligarchy to allow our managers to do what they do best; lead and innovate!

A Personal Perspective on the Future

There is massive potential for virtual wards and decentralised healthcare to revolutionise healthcare delivery from routine management of chronic disease to acute care. Although my virtual ward experience was rudimentary, it was developed in a time of unprecedented concern, never before experienced in human history. It is easy to criticise when this was developed in response to an acute need with very little opportunity for forethought and research, however it was revolutionary in its own way.

Although it holds great promise, we need a pragmatic, systematic and collaborative approach to ensure that this system works for everyone and adaptable processes suitable for advancements in the future. The financial burden on the NHS is significant and widely reported, with significant improvements to IT services within the NHS needed to ensure effective decentralised healthcare model implementation. It is unlikely given this current burden that the whole model will be implemented in entirety, but a hybrid model, where we use virtual wards as much as possible, augmenting face-to-face assessments. Developing a pragmatic approach to development and improvement within the realms of financial and technical capabilities will ensure this has the best possible beginning, improving patient experiences, safety and make it a beneficial method of healthcare delivery.

References

Blackpool Teaching Hospitals (2024) Virtual Wards. Available at: Virtual Wards :: Blackpool Teaching Hospitals

Hakim, R. (2023) Realising the Potential of Virtual Wards: Exploring the critical success factors for realising the ambitions of virtual wards. NHS Confederation [Online]. Available at: Realising the potential of virtual wards | NHS Confederation

Health Education England (2017) A Health and Care Digital Capability Framework. Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/eHealth/Digital-skills

Health Innovation Network South London (2021) Rapid Evaluation of Croydon Virtual Ward. Available at: Croydon-VW-Evaluation-Report-to-NHSX-v10.pdf

Lloyds Bank UK Consumer Index (2024) 2024 UK Consumer Digital Intex and Essential Digital Skills Report. Available at: https://www.lloydsbank.com/consumer-digital-index.html

National Audit Office (2020) Digital Transformation in the NHS. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/the-use-of-digital-technology-in-the-nhs/

NHS Digital (2024) Health Survey for England 2022, Part 2. Available at: Adults’ health – NHS England Digital

NHS England (2025a) Virtual Wards. Available at: Statistics » Virtual Ward

NHS England (2025b) Neighbourhood Health Guidelines 2025/26. Available at: NHS England » Neighbourhood health guidelines 2025/26

NHS England (2023) 2023/24 Priorities and Operational Planning Guidance. Available at: PRN00021-23-24-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v1.1.pdf

NHS England (2016) Understanding Patient Flow in Hospitals. Available at: patient_flow.pdf

NHS Inform (2024) Delirium. Available at: Delirium | NHS inform

Nuffield Trust (2020) Digital and remote care in the NHS during Covid-19. Available at: Digital and remote care in the NHS during covid-19 | QualityWatch

Ofcom (2024) Connected Nations Report. Available at: Connected Nations 2024 – Ofcom

Office for National Statistics (2023) Estimates of the very old, including centenarians, in England and Wales: 2002-2023. Available at: Estimates of the very old, including centenarians, England and Wales – Office for National Statistics

Royal College of Emergency Medicine (2022) Right Place, Right Care; Learning Lessons from the UK Crisis in Urgent and Emergency Care in 2022. Available at: RCEM_Acute_Care_in_2022_FINAL.pdf

DISCLAIMER

All views and opinions expressed in this post are solely my own and do not represent any organisation, including my employer. The educational practices and experiences discussed reflect my professional career to date, not exclusively my current role.

Leave a comment