This past week, I had the privilege of attending a dynamic academic roundtable, a gathering that brought together educators from a variety of professions and academic levels to grapple with one of the most pressing challenges facing modern education: the profound impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). The discussions were vibrant, ranging from the incredible potential of GenAI to transform learning experiences to the complex ethical tightropes we must navigate. It was a powerful reminder that while the future of AI in our classrooms is still being written, the questions it poses about how we learn, how we teach, and, crucially, how we assess, are immediate and urgent.

What struck me most throughout the debates was a recurring tension between the exciting possibilities AI offers for personalisation and efficiency, and the deep-seated anxieties it stirs regarding academic integrity and the very essence of what we aim to cultivate in our students: genuine learning and critical skills. These aren’t abstract concerns for distant futures; they are live dilemmas impacting classrooms nationwide right now. They demand careful consideration and proactive strategies from everyone dedicated to fostering genuine learning and a true enjoyment of learning. My reflections and research in this episode of The Educated Guess are deeply shaped by those conversations, aiming to explore the intricate relationship between GenAI, the concept of authenticity in student work, and the evolving landscape of assessment.

The Enduring Question: Assessing Capability in the Age of AI

An intriguing question a professor once posed to me was: ‘How do we truly know if we’re good at something?’ This query speaks to both internal validation – our personal sense of understanding and competence – and the crucial role of external validation. In our digital age, external validation takes many forms, from social media recognition to professional qualifications. Within healthcare, these qualifications are far from superficial; they represent a fundamental safeguard. We simply cannot permit nurses, doctors, or paramedics to practice without this critical ‘external validation’. The challenge, then, lies in how we effectively determine our students’ true capabilities, particularly with the rise of AI.

Historically, education has, perhaps too readily, leaned on assessment methods that are quick and easy to create, mark, and reuse – becoming the ‘lather, rinse, repeat’ of the education department (Boud & Falchikov, 2006, Lawrence, 2023). A traditional essay, for instance, requires minimal initial effort from the educator, a simple document repurposed across teams and cohorts. Yet, does this truly measure the hands-on application and complex reasoning demanded by clinical practice? In healthcare, our goal is for students to do the learning in context, not merely write about it. From the student’s perspective, we are increasingly inundating them with decontextualised knowledge, offering limited opportunities to grasp how complex biological systems genuinely interact (Kim et al, 2024, Tabatabaee, Jambarsang & Keshmiri, 2024). This preference for assessing recall over fostering deep reasoning places our current approaches at odds with the dynamic and often chaotic demands of the clinical frontline (Khong & Tanner, 2024).

As artificial intelligence and other transformative technologies now rapidly enter this sphere, we find ourselves at a critical crossroads regarding assessment (JISC, 2023). While some educators advocate integrating AI to support our existing educational assessment cycle—to aid students and clinicians in challenging times—a darker narrative warns of AI threatening our status quo (Wang et al, 2024, Balalle & Pannilage, 2025, QAA, 2024). This view largely focuses on GenAI enabling unprecedented cheating and plagiarism in written work (Birks & Clare, 2023). However, instead of solely reacting to this perceived threat, a more productive approach explores how GenAI can be genuinely integrated into pedagogical practices to support learning and more effectively prepare students for their future roles. The immediate challenge, then, is to fundamentally re-evaluate how we assess student capabilities within our evolving educational paradigms.

The Authenticity Imperative: Why We Must Adapt

The perceived threat of AI to academic integrity directly challenges a core tenet of our educational system: the authenticity of a student’s work (QAA, 2020, ACAI, 2021). Authenticity in a student’s work is crucial. Not only does it demonstrate their level of learning and understanding, and therefore their preparedness for real-world applications and employability skills, but it also provides a realistic picture of the student’s abilities. In this country, we operate within an educational system where authenticity is not only mandatory but rigorously celebrated and encouraged as a cornerstone of academic and professional development.

However, the value of the written form extends far beyond simply meeting academic attainment metrics. It is, fundamentally, a crucible for development of critical skills: problem-solving, critical thinking, and the ability to develop logical, persuasive, evidence-based arguments (Boud, 2001, Fischer et al, 2024). These essential real-world and academic competencies are precisely the skills that can be profoundly eroded by the unchecked or uncritical use of AI. If students consistently delegate the cognitive heavy lifting of ideation, structuring and articulation to AI, they risk what researchers call “cognitive offloading”, where their own capacity for deep, independent reasoning diminishes and academia creates written homogenisation (Peng & Leh, 2025, Xia et al, 2024, Werdiningsih, Marzuki & Rusdin, 2024). Recent studies have in fact shown a negative correlation between frequent AI usage and critical thinking abilities, particularly among younger individuals (Gerlich, 2025, Nosta, 2025).

This raises a profound question: If we allow the use of AI to undermine this concept, how can we ensure fairness across all students in achieving the same qualification, and how can we ensure authenticity in student work? In healthcare, where every decision can have life-or-death consequences, this isn’t merely an academic question; it’s a matter of patient safety and professional integrity.

The Global Classroom: Divergent Views on Authorship and AI

Our understanding of academic integrity is largely rooted in a Western scholastic tradition that champions individual authorship, originality, and meticulous citation. Yet, our classrooms are vibrant tapestries of global diversity, welcoming students from myriad cultural and educational backgrounds where these norms can diverge dramatically. In many cultures, the emphasis is less on individual originality and more on communal knowledge, collective learning, or the respectful reproduction of established wisdom (Hayes & Introna, 2005, Vance, 2021). For instance, rephrasing or summarising information from a trusted source might be viewed as a sign of respect or deep learning, rather than an act requiring explicit Western-style citation (Lei & Hu, 2024). Similarly, collaborative work might naturally blend individual contributions, making distinct delineation less critical. For students steeped in these different frameworks, the rigid Western rules of academic integrity can be confusing, isolating, and even feel culturally insensitive (Chan, 2024). They might genuinely struggle to grasp why using an AI tool to generate text is deemed ‘cheating,’ especially when their previous educational experiences didn’t prioritise unique individual textual production in the same way.

A common and legitimate challenge to educators is, “If educators use AI, why can’t I?” Educational institutions are increasingly employing AI for a variety of purposes (Robert, 2024) – from generating teaching materials to potentially marking assignments and giving feedback. If AI is trusted to evaluate learning, students can reasonably ask why they are not permitted to use it to demonstrate their learning. This highlights a critical need for transparency and consistency in the application of AI tools within the educational ecosystem. Students might also view AI as simply another advanced tool, akin to a calculator or spell checker, which are widely accepted and encouraged (JISC, 2025). This raises important questions about where to draw the line with GenAI, especially when educators themselves are exploring its potential.

Acknowledging these cultural and ethical complexities is not about lowering standards but about developing more nuanced and equitable approaches. It reinforces the need for open culturally sensitive dialogue and clear and consistent policies. Instead of focusing on detection, which is proving to be a losing battle, our energy must shift towards designing assessments that are inherently AI-resilient (Luo, 2025, JISC, 2024). This involves moving beyond easily replicable, product-focused assignments to methods that emphasise students’ unique cognitive processes, critical engagement, and real-world application. By developing these innovative methods of assessment, we can champion the ethical use of AI and essential digital skills while maintaining our core educational commitment: fostering genuine learning.

AI in Assessment: A Dual Approach

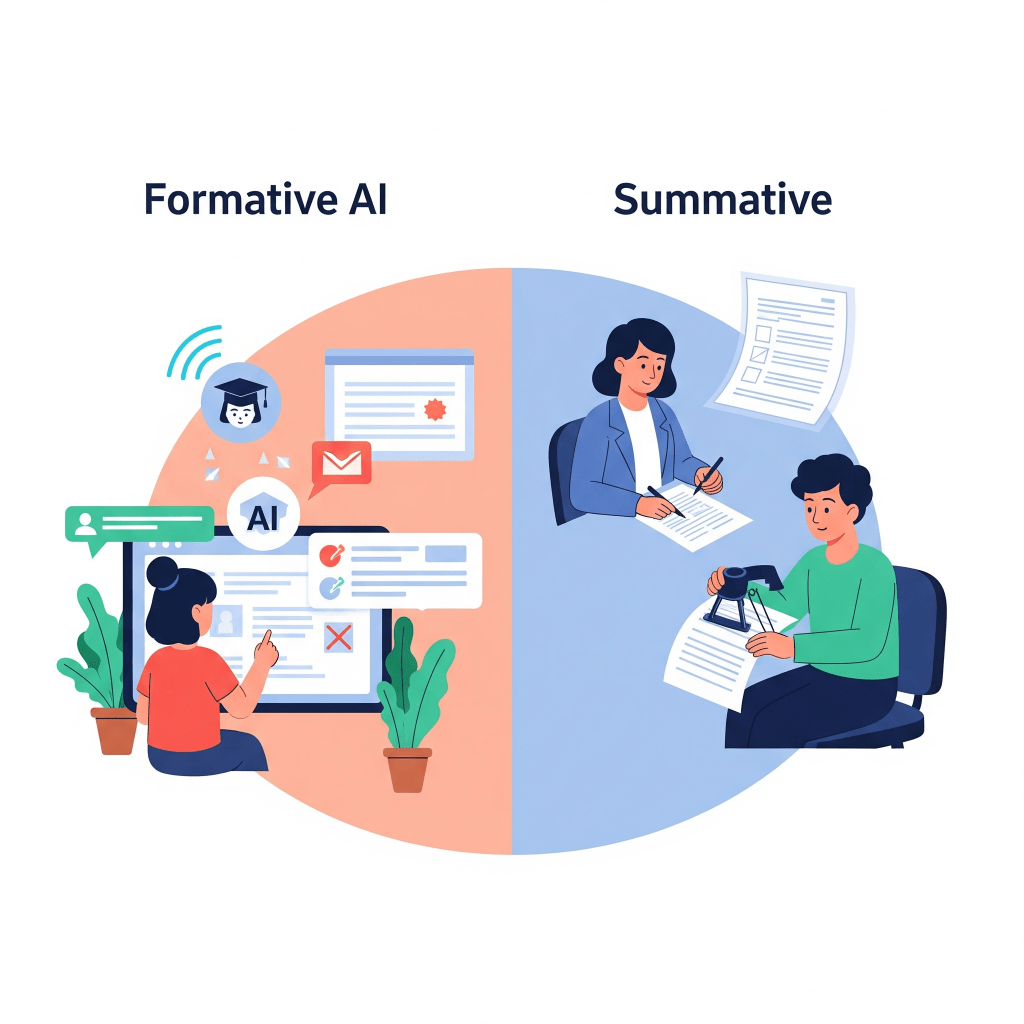

With low-stakes assessments (formative), AI provides a significant benefit. AI provides a powerful tool for monitoring learning, providing ongoing, personalised feedback. For students, this feedback helps improve their understanding and learning in real-time. For educators, it offers valuable insights to help refine their teaching strategies. This not only increases efficiency and reduces stress for both parties but also provides an adaptable and potentially cost-effective way to integrate AI into pedagogical practices (Bittle & El-Gayar, 2025).

The landscape changes dramatically, however, with high-stakes assessments (summative). These assessments are requirements for successful course completion, often determining a student’s overall mark and final qualification. Traditionally, these have heavily focused on the written form, demanding students develop critical skills essential for the workforce and progression into higher levels of academia.

Alongside the cultural dilemmas we’ve already explored, there are considerable ethical quandaries around using AI to mark student work. While AI offers tempting efficiencies for large cohorts and boasts objectivity in certain tasks, which can be very useful for time-restricted educators, it currently lacks the sophistication to detect and understand the nuanced decisions and complex judgements required in academic work. This limitation is even more critical in fields like healthcare, where clinical judgement demands a profound, context-dependent level of nuance, often involving verbal cues, adapting to chaotic situations, and making high-stakes decisions where human empathy, ethics and experience are irreplaceable. There’s also a tangible risk of AI introducing new problems or errors, which the educator then has to meticulously unpick and solve, often negating any efficiency gains.

Personally, I’m all for exploring how AI can help with formative assessments and genuinely improve learning. However, with summative assessments, I am considerably more cautious. I have discussed a few reasons already, but ultimately, if I, as an educator and professional, am responsible for the mark given, then I want to read the assignment. Authenticity to me works both ways: it’s not just about the student’s work being authentic but also about my integrity and professionalism as an assessor. I don’t want to risk making a mistake or having my judgement questioned because I’ve relied uncritically on AI, which I believe is highly possible to do when time-poor.

The Persuasive Problem of Bias in AI Marking

Building on these ethical quandaries, a particularly concerning aspect of using AI for summative assessment is the pervasive issue of algorithmic bias (Chen, 2023), Panch, Mattie & Atun, 2019, Boateng & Boateng, 2025). As GenAI models are trained on large datasets, any cultural, societal or historical prejudices embedded in that data, can be perpetuated and potentially amplified. Moreover, AI’s reliance on algorithms means it lacks the nuanced judgement that humans provide, often resulting in “stiff” or superficial prose. This dynamic risks encouraging students to “please the algorithm” rather than developing genuine understanding. Compounding this, the so-called “black box” problem– where the internal workings of AI grading systems are opaque – undermines trust by limiting educators’ ability to understand, identify and rectify biases (Hanhui & Shuttleworth, 2024). To address this, AI systems in education should be designed as “glass boxes”, with transparency a core component built in from the outset (Tubella et al, 2019).

The integration of GenAI into education also raises significant concerns regarding privacy and data security. If institutions use GenAI tools not specifically designed for educational purposes, they risk exposing confidential student information (e.g., IDs, grades, personal details) which could then be used to train models accessible to others (Mellado, 2024). This ubiquitous data collection, often involving more information than explicitly stated and sometimes collected subtly or without full awareness, clashes directly with the UK’s stringent GDPR guidelines, particularly its principle of ‘data minimisation.’ Even prompts containing demographic or personal details risk an aggregated reproduction that could link back to individuals, presenting real risks both now and in the future (Sartor, 2024, Balasubramaniam et al, 2023).

Further exacerbating these concerns is the storage of student data by external GenAI tools or cloud services, raising critical questions about data ownership, precise storage locations, and who maintains access. For instance, while a service like Google Gemini might claim to store data within the US and Europe, the specific jurisdiction matters; processing in countries with less stringent data protection laws, or where enforcement is more challenging, directly conflicts with UK GDPR guidelines. This creates significant legal and ethical vulnerabilities.

Moreover, the sheer volume of student data collected holds considerable commercial value. The vast amounts of data could potentially be sold or monetised by EdTech companies, leading to profound privacy erosion and a breakdown of trust. This constant pervasive monitoring can also foster what is known as the “Big Brother Effect”, where the persistent feeling of being watched can stifle academic freedom, inhibits genuine inquiry and potentially lead to behavioural changes or mental health issues in students (Seymour, McNicholl & Koenig-Robert, 2024).

Amid these challenges, the “arms race” of GenAI forces us to rethink traditional written work and how the concept of authenticity in assessment (DoE, 2024). This is a challenging shift, as practical and theoretical differences will exist across courses, and nearly all academic qualifications demand some form of extensive written work, such as a dissertation or theses, to meet their requirements. This raises critical questions: How can we ensure we develop critical skills – problem solving, critical thinking and logical argumentation – if we reduce or move away from written work as a primary assessment method? And, if we move away completely from fostering rigorous written communication, are we inadvertently setting students up for a disadvantage when they try to complete the entrenched requirements of gateway qualifications like BSc, MSc or PhD degrees?

Finding Our Balance: A Human-Centred Future for AI in Assessment

Our path forward demands a strategic shift away from the “arms race” of detection towards proactive, AI-resilient assessment design (Gonsalves, 2025). This means leveraging AI to provide personalised formative support while radically rethinking summative assessments to prioritise process over product. To truly assess a student’s capabilities in the digital age, we must test higher order skills that AI cannot replicate (as described in Bloom’s Taxonomy below).

Image Source: Blooms Taxonomy Revisited: Oregon State University.

Crucially, we must reframe the narrative surrounding AI’s impact on critical thinking. While unchecked use can encourage cognitive offloading, educators have a unique opportunity to model and teach critical AI engagement. AI’s ability to rapidly generate diverse perspectives and synthesise vast amounts of information challenges students to practice discernment and synthesis-core components of critical thinking. Furthermore, the very issues AI presents, like bias and hallucinations, coupled with its unprecedented speed, create powerful learning opportunities. Teachers can model how to craft effective prompts, critically evaluate AI outputs for accuracy and bias, and leverage AI for deeper inquiry rather than just quick answers, thereby directly fostering essential digital literacy and transforming AI from a potential crutch into a powerful catalyst for learning.

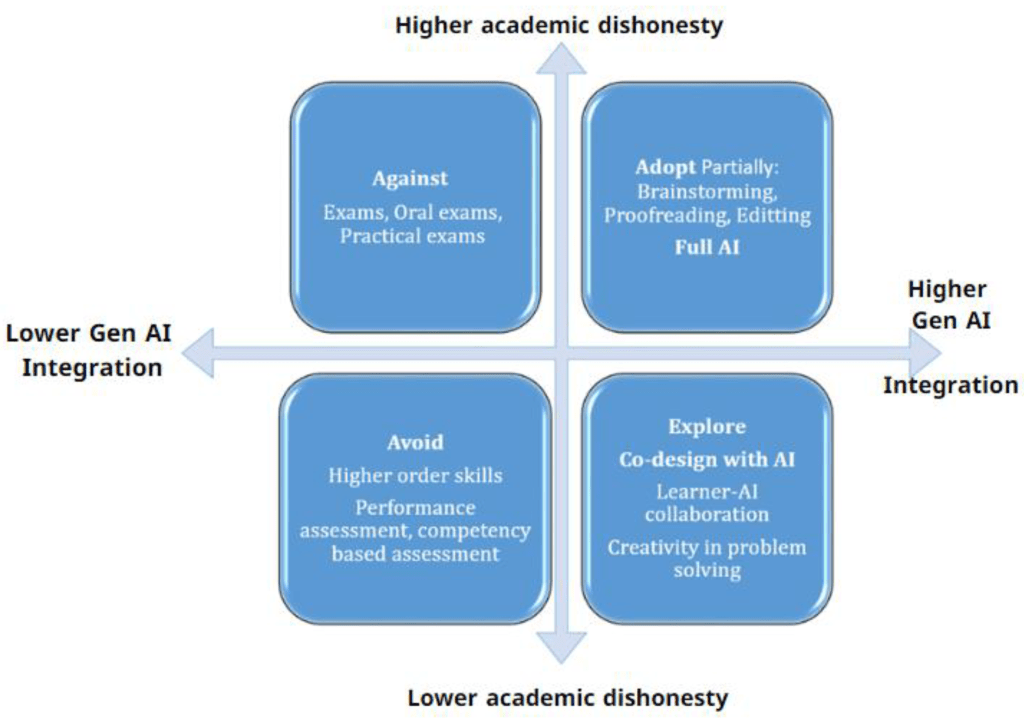

Moving beyond relying exclusively on written work by incorporating diverse methods using the Against, Avoid, Adopt, Explore (AAAE)(Khlaif et al, 2025) framework is key to AI resilience. These can include:

- Oral examinations or viva voce – a rich assessment method where a student must prepare an oral defence of their research/project/essay and so requires the ability to discuss complex concepts with nuance, defend arguments, and synthesise information.

- Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) – These semi-simulated scenarios require students to perform a skill or set of skills in real time, with a simulated mannikin or patient. This demonstrates application of knowledge and skill to a specific context, integrating multiple other skills essential to various areas of practice e.g. communication, rapport building, ethics, professional values, decision making, infection control.

- Capstone Projects – these usually involve an element of research and practical application with a written write up of the entire project. This aligns with the higher order thinking as well as the development of a professional portfolio.

- Presentations – Like the oral examinations, presentations allow for demonstration of understanding beyond recall and application to practice. Follow up question & answer sessions require students to address challenges, defend arguments and integrate with verbal and non-verbal communication and creativity in their accompanying visuals.

- Debates – This assessment method is a particularly interesting choice. Whilst forming a significant component of day-to-day professional life, are rarely utilised in assessment, yet they offer substantial value. It would be easy to demonstrate process over product here, demonstrating the students work to prepare for the debate being key. Integration of complex and unpredictable topics make it AI-resilient if topics that AI can’t provide pre-packaged answers are chosen.

Image: The Against, Avoid, Adopt, Explore (AAAE) framework posed as a theoretical framework to adopt AI resilient assessments. (Khlaif et al, 2025)

Maintaining some written work remains important to prevent loss of academic skills, but we must consider a rethink around student motivation. Instead of solely focusing on a qualification (extrinsic motivation) or writing for professors, we should align written tasks with tangible, real-world outcomes – such as preparing manuscripts for academic journals, developing policy briefs for healthcare authorities, or contributing to patient care guide. By shifting the focus from mere qualification (extrinsic motivation) to genuine purpose we can drive deeper engagement and effort, naturally fostering critical thinking, problem-solving, and argumentation skills, thereby cultivating authentic employability and professional competencies. This would also help to avoid the double standards in practice explored earlier.

Furthermore, clear institutional policies and guidelines are essential, offering specific boundaries on when and where AI is permissible, perhaps through a “traffic light” system, and demanding explicit attribution and documentation to maintain fairness and authenticity. This provides crucial clarity for students’ expectations and establishes a framework for recourse when academic integrity offenses arise (UOL, 2024).

Ultimately, while AI offers powerful tools, the heart of education remains fundamentally human. It is our human judgement, our capacity for empathy, creativity, critical reasoning, and adaptive problem-solving that remains paramount, especially in fields like healthcare, where lives are at stake. By embracing thoughtful integration, designing innovative assessments, and crucially, redefining the motivation behind learning itself, we can ensure our academic and professional futures remain bright and fit for purpose.

References

Balasubramaniam, N., Kauppinen, M., Rannisto, A., Hiekkanen, K., Kujala, S. (2023) Transparency and explainability of AI systems: From ethical guidelines to requirements. Information and Software Technology, 159. 107197. DOI: 10.1016/j.infsof.2023.107197

Ballale, H. & Pannilage, S. (2025) Reassessing academic integrity in the age of AI: A systematic literature review on AI and academic integrity. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, Volume 11, 101299. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2025.101299

Birks, D., Clare, J. Linking artificial intelligence facilitated academic misconduct to existing prevention frameworks. Int J Educ Integr 19, 20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00142-3

Bittle, K., & El-Gayar, O. (2025). Generative AI and Academic Integrity in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Information, 16 (4), 296; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040296

Boateng, O. & Boateng, B. (2025) Algorithmic bias in educational systems: Examining the impact of AI-driven decision making in modern education. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews. 25(01), 2012-2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2025.25.1.0253

Boud, D. (2001). Using journal writing to enhance reflective practice. In English, L. M. and Gillen, M. A. (Eds.) Promoting Journal Writing in Adult Education. New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education No. 90. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Boud, D. & Falchikov, N. (2006) Aligning assessment with long-term learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 31 (4), 399-413. DOI: 10.1080/02602930600679050

Chan, C.Y.K. (2024) Students’ perceptions of ‘AI-giarism’: investigating changes in understandings of academic misconduct. Educ Inf Technol 30, 8087-8108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13151-7

Chen, Z. Ethics and discrimination in artificial intelligence-enabled recruitment practices. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 567 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02079-x

Department of Education (2024) Generative AI in Education, Educator and Expert Views. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/generative-artificial-intelligence-in-education/generative-artificial-intelligence-ai-in-education

Fischer, J., Bearman, M., Boud, D., Tai, J. (2024) How does assessment drive learning? A focus on students’ development of evaluative judgement. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 49 (2), pp. 233-245.

Gerlich, M. (2025) AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=5082524

Gonsalves, C. (2024). Contextual Assessment Design in the Age of Generative AI. Journal of Learning and Development in Higher Education. 34; DOI: https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi34.1307

Hanhui, X. & Shuttleworth, K.M.J (2024) Medical artificial intelligence and the black box problem: a view based on the ethical principle of “do no harm”. Intelligent Medicine, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2024, Pages 52-57, ISSN 2667-1026, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imed.2023.08.001.

Hayes, N. & Introna, L.D. (2005) Cultural Values, Plagiarism and Fairness: When Plagiarism gets in the way of learning. Ethics & Behavior, 15(3): 213-231.

International Center for Academic Integrity (ACAI) (2021) The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity 3rd edn. Available at: www.academicintegrity.org/the-fundamental-valuesof-academic-integrity

JISC (2025) Student Perceptions of AI 2025. Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/student-perceptions-of-ai-2025

JISC (2023) Artificial Intelligence (AI) in tertiary education. Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/artificial-intelligence-in-tertiary-education

Khong, M.L. & Tanner, J.A. (2024) Surface and Deep learning: a blended learning approach in preclinical years of medical school. BMC Medical Education, 24, 1029. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05963-5

Khlaif, Z.N., Alkouk, W.A., Salama, N., Eideh, B.A. (2025) Redesigning Assessments for AI-Enhanced Learning: A Framework for Educators in the Generative AI Era. Educ. Sci. 15(2), 174; https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020174

Kim, M., Duncan, C., Yip, S., Sankey, D. (2024) Beyond the theoretical and pedagogical constraints of cognitive load theory, and towards a new cognitive philosophy in education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2024.2441389

Lei, J. & Hu, G. (2024) Investigating Plagiarism in Second Language Writing. Cambridge University Press.

Luo, J. (2024) A critical review of GenAI policies in higher education assessment: a call to reconsider the “originality” of students’ work . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(5), 651–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2309963

Mellado, R. (2024) Risks of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Critical Perspective. International Journal of Advanced in Engineering and Management (IJAEM). 6(9), pp: 226-238.

Nosta, J. (2025)The Shadow of Cognitive Laziness in the Brilliance of LLMs. Psychology Today. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-digital-self/202501/the-shadow-of-cognitive-laziness-in-the-brilliance-of-llms

Panch, T., Mattie, H., Atun, R. (2019) Artificial intelligence and algorithmic bias: implications for health systems. J Glob Health. Dec;9(2):010318. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020318. PMID: 31788229; PMCID: PMC6875681.

Peng, J. L., & Yeh, S. L. (2025). Cognitive Offloading in Short-Term Memory Tasks: Trust Toward Tools as a Moderator. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2025.2474449

QAA (2024) Quality Compass: Navigating the complexities of the artificial intelligence era in higher education. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/sector-resources/generative-artificial-intelligence/qaa-advice-and-resources

QAA (2020) Academic Integrity Charter for UK Higher Education. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk//en/sector-resources/academic-integrity/charter

Robert, J. (2024) The Future of AI in Higher Education. Educause AI Landscape Study. Available at: https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/2024/2024-educause-ai-landscape-study/the-future-of-ai-in-higher-education

Sartor, G. (2020) The impact of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on Artificial Intelligence. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/641530/EPRS_STU(2020)641530_EN.pdf

Seymour, K., McNicholl, J., Koenig-Robert, R. (2024) Big brother: the effects of surveillance on fundamental aspects of social vision. Neuroscience of Consciousness, (1). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nc/niae039

Tabatabaee, S.S., Jambarsang, S. & Keshmiri, F. Cognitive load theory in workplace-based learning from the viewpoint of nursing students: application of a path analysis. BMC Med Educ, 24, 678 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05664-z

Tubella, A.A., Theodorou, A., Dignum, F., Dignum, V. (2019) Governance by Glass-Box: Implementing Transparent Moral Bounds for AI Behaviour. Conference: International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2019/802

University of Leicester (2024) Policy on Generative Artificial Intelligence in Learning. Available at: https://le.ac.uk/-/media/uol/docs/policies/quality/ai-policy.pdf

Wang, S., Wang, F., Zhu, Z., Wang, J., Tran, T., Du, Z. (2024) Artificial Intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Systems with Applications, Volume 252 Part A, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124167.

Vance, N (2021) Cross-cultural perspectives on source referencing and plagiarism. EBSCO Available at: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/ethnic-and-cultural-studies/cross-cultural-perspectives-source-referencing-and

Werdiningsih, I., Marzuki, & Rusdin, D. (2024). Balancing AI and authenticity: EFL students’ experiences with ChatGPT in academic writing. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2024.2392388

Xia, Q., Weng, X., Ouyang, F. et al. A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. Int J Educ Technol High Educ, 21, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00468-z

DISCLAIMER

All views and opinions expressed in this post are solely my own and do not represent any organisation, including my employer. The educational practices and experiences discussed reflect my professional career to date, not exclusively my current role.

Leave a comment